When Bugatti broke the 300mph barrier with the Chiron last year, it looked like a record that might stand forever. Reaching the unlikely peak of 304.77mph had required considerable engineering effort – and the creation of what became the Chiron 300+ special edition – but also exclusive use of the 12-mile high-speed track at Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien proving ground in Germany.

It took driver Andy Wallace nearly a week to build up to the record speed, and he only reached his target on the final run of the last day. When Bugatti boss Stephan Winkelmann announced the record, he also said the firm wouldn’t seek to defend it.

Then in October, relative minnow SSC from the US announced that it had not just broken the Chiron’s record but smashed it. Its 1750bhp Tuatara, running on public roads in Nevada, had reportedly been driven to a two-way average of 316.11mph by British racer Oliver Webb, having hit 331.15mph in one direction.

That seemingly impossible figure soon had internet sleuths exhaustively analysing the video footage of the run, with some reckoning the car hadn’t gone nearly as fast. SSC stands by its numbers, blaming a video editing error, but boss Jerod Shelby has now said his company will answer the doubters by doing the whole thing again.

This interview with Wallace took place last September, when his claim to be the world’s fastest man in a production car was still undisputed. The 59-year-old Brit is actually a two-time holder of the record, having driven the McLaren F1 to 240.1mph in 1998, with his career highlights also including an outright win at the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1988.

Frenchman Pierre-Henri Raphanel, who is also 59 and a successful sports car racer and Le Mans victor (1997), drove the Bugatti Veyron Super Sport to its record 267.9mph in 2010. These days, both he and Wallace work for Bugatti as ambassadors and test drivers.

Both have well-stocked trophy cabinets at home and are quick to acknowledge that travelling quickly in a production car is less challenging than sharp-end motorsport. But the risks of going so fast are still very real.

“It’s a mental exercise,” says Raphanel. “It’s a straight line and you have to stay straight and keep the power on. But you also know that if anything is happening at that speed, you’re unlikely to come back to the engineer to say ‘there was something wrong’. It’s more likely that you will not come back.”

“You do think about the risks, but not when you’re actually driving,” Wallace adds. “You need to have confidence in the car but also in the people who have built it and who are looking after the stuff you can’t control.”

Any record attempt brings the weight of expectations. Raphanel says he was given a target based on what Bugatti’s engineers believed the car was capable of: more than 425kph (264mph). “But you arrive on the day of the record and there are 100 people there – you can’t go ‘sorry guys, I don’t feel like doing it today’,” he says. Wallace’s Chiron run nine years later came with a substantially higher target – that of breaking the 300mph barrier. The big issue being, as he explains, that entering the last day the top speed had stalled at a tantalisingly close 299.8mph. That, as he admits, “would have been a PR disaster”.

Both runs were carried out at Ehra-Lessien, with ultra-high speeds magnifying the effect of even tiny imperfections in the ultra-smooth surface. Raphanel’s attempt was done to satisfy the requirement for a two-way average. “You realise that just going the opposite way to the direction the track is used in makes a difference,” he remembers. “It’s like when you shave the wrong way: one way is smooth and the other is like the Tarmac makes little teeth, and these change the way the car feels and behaves.”

Going essentially the wrong way also negated the effectiveness of much of Ehra-Lessien’s carefully designed protection system. The high-speed track has a single barrier where speeds are lowest, rising to double then triple height along the REF straight. So on his reverse run, Raphanel’s peak speed came with the least protection. “If anything had happened where the speed was highest, I would have been in the forest,” he says.

Wallace went in only one direction, as Volkswagen subsequently decided to ban wrong-way high-speed running on safety grounds. But the Chiron’s greater velocities still revealed a more dramatic issue: a join between two different track surfaces that Wallace began to call ‘the jump’. “The engineers didn’t believe me,” he says, “then they looked at the data and realised that when the car was hitting it at 447kph (277.8mph) or so, it really was taking off.”

Any pioneer has to venture into the unknown – something that became more of an issue to Wallace as the Chiron’s peak speeds rose. “Before long at 400kph (248.5mph), my heart rate was normal, because we did 1000km (621 miles) of testing during the week to validate the simulated aero numbers that Dallara had done, and most of it was around there,” he says. “400kph still felt really calm and comfortable. But 450kph (279.6mph) never did.”

Wallace grew used to ‘the jump’ and to the tendency of the Chiron to wander on the more worn track surface that followed it, as well as the increasing influence of even modest crosswinds. But as the speeds rose, he found himself facing a new and unfamiliar one: the gyroscopic forces developed by the huge rotational speeds of the Chiron’s wheels.

“I’d liken it to a child’s spinning top,” Wallace explains. “When you steer a car normally, you have some self-centring from the caster. But the gyroscopic forces mean that if the car is going left, it wants to carry on and will continue until you make another input. So you steer the other way and, unless you get it perfect, the effect is magnified.”

That’s why the limiting factor for the Chiron wasn’t performance but rather Wallace’s confidence in keeping it on the road. “By the Thursday night, I was stuck. I just couldn’t go faster because, every time I reached that speed, I needed all three lanes,” Wallace remembers. “Over dinner, I said: ‘I’m just going to stay with my foot on the floor tomorrow until it passes the magic number, even if that means it’s too late to slow down for the banking. I’m going to do that because you can’t have a supercar that goes 299.8mph.’”

Fortunately, it didn’t come to that. On his final run, Wallace carried more speed onto the straight than he had before, felt more confident after the jump, then stayed flat out for as long as he dared (“at 135 metres per second, it’s really hard to judge braking distances”), slowing down just enough for the banking at the far end of the track and returning to the staging area to discover that he had managed nearly 305mph.

Raphanel acknowledges that setting his record was considerably less fraught but admits to having had worries about tyre life. He explains: “They had tested them on a bench machine at 435kph (270.2mph), because that’s all the machine could do: 435kph and a 20-second cycle. They said after six cycles, the tyres will probably explode, which of course means two minutes. But then when I broke the record, I noticed that the tyres were the same as I had used the day before; they said ‘you’re still in the window’. All I could do was hope: it’s not a window you want to fall out of.”

Bugatti says that it won’t defend its title, but if the company were to change its mind, would either of its record-setters be tempted to try again if Winkelmann phoned to offer them another go?

“‘Hello? Hello? Stephan? It’s a bad line, I can’t hear you,’” jokes Raphanel. “Personally, I was very happy to do this, to be part of history – but in my case, one time was enough. We did the records to show that Bugattis are the best cars in the world, not because we’re the best drivers.”

“When you’re a racing driver, if somebody asks you a question like that, you’ll always put on this persona of everything being good and say ‘bring it on’,” adds Wallace. “It’s easy to stand here knowing that we’re not going to do it and say ‘of course I would’. But in reality, it’s not just a straight yes: I would seriously have to think about it. It’s not just a walk in the park.”

The 10 fastest production cars (sort of)

While overall speed records are recorded and verified by the FIA, the production car title has always been subject to looser criteria and, like boxing, runs under what are effectively a variety of codes and self-appointed sanctioning bodies.

The big ideological division is now one that dates to the very beginning of record-setting: whether a car needs to run a course in two directions for an average time. Although Pierre-Henri Raphanel’s Bugatti Veyron Super Sport record was run in two directions at Ehra-Lessien, Volkswagen has since stopped these, meaning that two-way runs can only take place on either lesser tracks or public roads. Guinness World Records recognised Raphanel’s run as a record but not Andy Wallace’s later effort; instead, the Chiron’s time was validated by Germany’s TUV Technical Inspection Association.

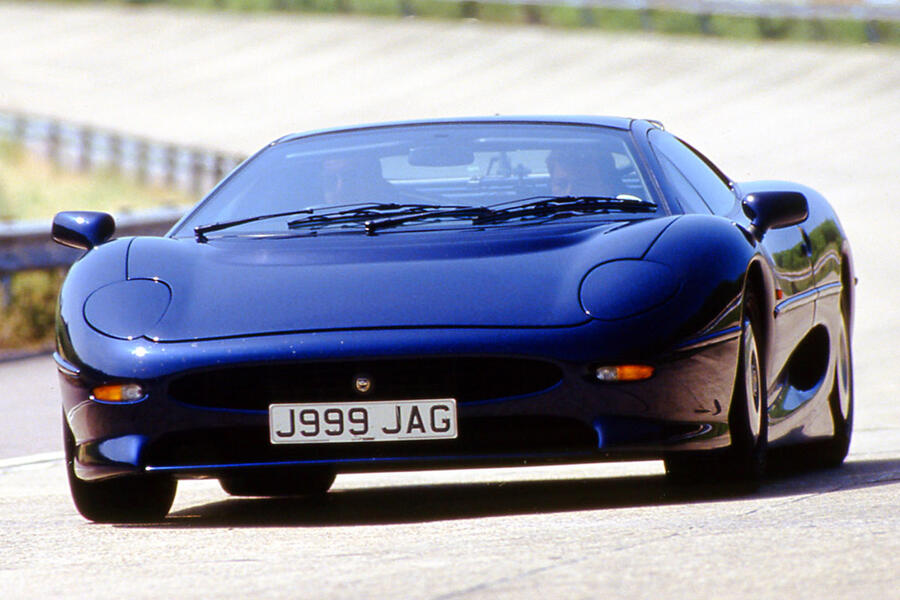

Production status is another thorny issue, with some dissent as to whether the record-setting Chiron qualified; the modifications carried out to it inspired a Super Sport 300+ limited run, but it came after the record was set. The SSC Tuatara also struggles with the definition, as no customer cars have been delivered yet. Then there’s the matter of permitted modification, which was more liberal in the past; the acknowledged records of both the Jaguar XJ220 and McLaren F1 were set with raised rev limits.

With that in mind and with copious use of provisos, here are the top 10.

1 - SSC Tuatara

Year 2020 Speed 316.11mph Driver Oliver Webb Location Public road, Nevada, US Guinness World Record? No Proviso Claimed and awaiting verification. SSC plans to repeat due to controversy

Year 2019 Speed 304.77mph Driver Andy Wallace Location Ehra-Lessien, Germany GWR? No

Year 2017 Speed 277.87mph Driver Niklas Lilja Location Public road, Nevada, US GWR? No Proviso Record request submitted but seemingly never given

Year 2014 Speed 270.49mph Driver Brian Smith Location Kennedy Space Center, Florida, US GWR? No Proviso Not really series-production

Year 2010 Speed 267.9mph Driver Pierre-Henri Raphanel Location Ehra-Lessien, GWR?

Year 2007 Speed 256mph Driver Chuck Bigelow Location Public road, Washington, US GWR? Yes

7 - Bugatti Veyron

Year 2005 Speed 253.8mph Driver Uwe Novacki Location Ehra-Lessien, Germany GWR? No

8 - Koenigsegg CCR

Year 2005 Speed 241.1mph Driver Loris Bicocchi Location Nardò, Italy GWR? Yes Proviso Rev limit raised and no cats

9 - McLaren F1

Year 1998 Speed 240.1mph Driver Andy Wallace Location Ehra-Lessien, Germany GWR? Yes Proviso Rev limit raised, having previously done 231mph

10 - Jaguar XJ220

Year 1992 Speed 217.1mph Driver Martin Brundle Location Fort Stockton, Texas, US GWR? Yes Proviso Rev limit raised and no cats

No comments:

Post a Comment